유클리드 원론 5권

수학이야기/유클리드원론 2015. 4. 13. 11:50유클리드 원론 5권

Definitions

Definition 1 A magnitude is a part of a magnitude, the less of the greater, when it measures the greater.

크기는 작은 것으로 큰 것을 측정했을 때, 큰 것보다 작은 크기의 부분이다. (magnitude는 선분의 길이, 각의 크기, 도형의 넓이와 같이 종류가 같은 것을 측정한 것인데 일단 크기로 옮기자.)

Definition 2 The greater is a multiple of the less when it is measured by the less.

큰 것은 작은 것으로 측정되었을 때, 작은 것의 배수이다. 어떤 크기가 다른 작은 크기에 자연수를 곱한 것과 같다면 큰 것은 작은 것의 배수라는 말이다.

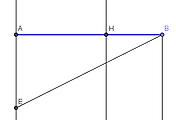

아래 그림과 같을 때 $a$로 $b$를 측정하여 $3a=b$를 얻을 것이다. 이때 $a$는 $b$의 부분이고 $b$는 $a$의 배수이다.

Definition 3 A ratio is a sort of relation in respect of size between two magnitudes of the same kind.

비는 같은 종류의 크기 사이의 치수에 관한 관계의 한 종류이다. (size는 크기를 잰 값으로 치수로 옮긴다.) 같은 종류라 함은 주어진 두 크기가 길이와 길이, 넓이와 넓이, 부피와 부피처럼 같이 양을 나타냄을 말한다. 오늘날은 두 크기가 이루는 비를 쌍점을 써서 a:b와 같이 쓴다.

Definition 4 Magnitudes are said to have a ratio to one another which can, when multiplied, exceed one another.

크기는 어떤 것의 적당한 배수가 다른 것을 초과한다면 비를 가진다고 말한다. 길이가 무한한 직선이 있다면 유한한 길이를 늘려서 초과할 수 없고 한 없이 작은 길이를 가진 직선은 늘릴 수 없다. 따라서 이 정의는 크기가 무한소나 무한대인 것을 배제하고 있다.

Definition 5 Magnitudes are said to be in the same ratio, the first to the second and the third to the fourth, when, if any equimultiples whatever are taken of the first and third, and any equimultiples whatever of the second and fourth, the former equimultiples alike exceed, are alike equal to, or alike fall short of, the latter equimultiples respectively taken in corresponding order.

다음을 만족하면 크기는 첫째와 둘째 그리고 셋째에서 넷째는 비가 같다고 한다. 첫째와 셋째에 같은 수를 곱하고 둘째와 넷째에 또 다른 같은 수를 곱할 때, 앞에 있는 배수가 뒤에 있는 배수를 각각 있는 순서대로 똑같이 초과하거나, 같거나, 작다.

모든 수 $m,\;\;n$에 대하여 다음과 같이 대소 관계가 그대로 유지된다면 비례식 $w:x=y:z$라고 한다.

1) $mw>nx$이면 $my>nz$이다. 2) $mw=nx$이면 $my=nz$이다. 3) $mw<nx$이면 $my<nz$이다.

Definition 6 Let magnitudes which have the same ratio be called proportional.

비가 같은 크기는 서로 비례한다고 한다.

Definition 7 When, of the equimultiples, the multiple of the first magnitude exceeds the multiple of the second, but the multiple of the third does not exceed the multiple of the fourth, then the first is said to have a greater ratio to the second than the third has to the fourth.

같은 배수에서 첫째 크기의 배수가 둘째 크기의 배수를 초과하는데 셋째 크기의 배수가 넷째 크기의 배수를 초과하지 않을 때 첫째는 둘째의 비가 셋째와 넷째의 비보다 크다고 한다.

$nw > mx$이지만 $ny\leq mz$인 수 $n,m$이 존재하면 $w:x > y : z $라고 한다.

Definition 8 A proportion in three terms is the least possible.

세 항의 비례가 가능하다. $a:b=b:c$가 가능하다는 말이다.

Definition 9 When three magnitudes are proportional, the first is said to have to the third the duplicate ratio of that which it has to the second.

세 크기가 비례할 때, 첫째와 셋째의 비는 첫째와 둘째의 비의 '제곱비'이다. $a:b=b:c$이면 $a:c$는 $a:b$의 '제곱비'라고 부른다. $$a:b=b:c\Rightarrow a:c=a^2:b^2$$

Definition 10 When four magnitudes are continuously proportional, the first is said to have to the fourth the triplicate ratio of that which it has to the second, and so on continually, whatever be the proportion.

네 크기가 연속적으로 비율이 같다면 첫째 넷째의 비는 첫째와 둘째의 비의 '세제곱비'라고 말한다.

$$a:b=b:c=c:d\quad \Rightarrow \quad a:d=a^3:b^3$$

Definition 11 Antecedents are said to correspond to antecedents, and consequents to consequents.

전항은 전항과 후항은 후항과 관련되었다고 말한다. ($a:b=$전항:후항)

Definition 12 Alternate ratio means taking the antecedent in relation to the antecedent and the consequent in relation to the consequent.

교대비는 전항끼리와 후항끼리의 비를 뜻한다. $a:b=c:d$일 때, $a:c=b:d$.

Definition 13 Inverse ratio means taking the consequent as antecedent in relation to the antecedent as consequent.

역비는 전항과 후항을 바꾼 것이다. $a:b$의 역비는 $b:a$이다.

Definition 14 A ratio taken jointly means taking the antecedent together with the consequent as one in relation to the consequent by itself.

공동으로 취한 비는 전항과 후항을 더한 것과 후항의 비이다. $u:v$에서 공동으로 취한 비는 $u+v:v$이다.

Definition 15 A ratio taken separately means taking the excess by which the antecedent exceeds the consequent in relation to the consequent by itself.

분리 비는 후항과 관련하여 전항이 후항을 초과하는 부분을 전항으로 취하는 비이다. $u+v:v$에서 $u:v$를 취하는 것이다.

Definition 16 Conversion of a ratio means taking the antecedent in relation to the excess by which the antecedent exceeds the consequent.

비의 변환은 전항이 후항을 초과하는 것을 후항으로 취하는 것을 의미한다. $u+v:v$의 변환은 $u+v:u$이다.

Definition 17 A ratio ex aequali arises when, there being several magnitudes and another set equal to them in multitude which taken two and two are in the same proportion, the first is to the last among the first magnitudes as the first is to the last among the second magnitudes. Or, in other words, it means taking the extreme terms by virtue of the removal of the intermediate terms.

라틴어라 우리말로 옮기기 어렵네.. 평등(aequali), 에서(ex), 비(ratio).

현대적인 식으로 표현하면 아래와 같다.

양의 실수인 $\alpha_1, \; \alpha_2\;,\cdots,\;\alpha_n$와 $\beta_1 ,\;\beta_2,\;\cdots,\;\beta_n$ 사이에 아래와 같은 관계가 성립한다면

$$\frac{\alpha_1}{\alpha_{2}}=\frac{\beta_1}{\beta_{2}},\quad\frac{\alpha_2}{\alpha_{3}}=\frac{\beta_2}{\beta_{3}},\quad\ldots,\quad\frac{\alpha_{n-1}}{\alpha_{n}}=\frac{\beta_{n-1}}{\beta_{n}}$$

평등비(ratio ex aequali)는 아래 방정식이다. $$\frac{\alpha_1}{\alpha_{n}}=\frac{\beta_1}{\beta_{n}}$$

Definition 18 A perturbed proportion arises when, there being three magnitudes and another set equal to them in multitude, antecedent is to consequent among the first magnitudes as antecedent is to consequent among the second magnitudes, while, the consequent is to a third among the first magnitudes as a third is to the antecedent among the second magnitudes.

양의 실수인 $\alpha_1,\alpha_2,\alpha_3$와 \(\beta_1,\beta_2,\beta_3\)사이에 아래와 같은 비례식이 성립하면 방해 비율(perturbed proportion)이 생겨난다.

\[\frac{\alpha_1}{\alpha_{2}}=\frac{\beta_2}{\beta_{3}},\quad\frac{\alpha_2}{\alpha_{3}}=\frac{\beta_1}{\beta_{2}}.\]

다르게 적으면 아래와 같다. $$\frac{\alpha_1}{\alpha_{3}}\not=\frac{\beta_1}{\beta_{3}} $$

Propositions

Proposition 1 If any number of magnitudes are each the same multiple of the same number of other magnitudes, then the sum is that multiple of the sum.

크기를 나타내는 수들이 크기를 나타내는 다른 수에 각각 같은 자연수를 곱한 배수라면 그 수들의 합은 다른 수들의 합의 배수이다.

* 크기를 나타내는 수 $x,\;\;y$와 자연수 $m$에 대하여 $mx+my=m(x+y)$

Proposition 2 If a first magnitude is the same multiple of a second that a third is of a fourth, and a fifth also is the same multiple of the second that a sixth is of the fourth, then the sum of the first and fifth also is the same multiple of the second that the sum of the third and sixth is of the fourth.

첫째 크기는 둘째 크기 c의 배수 mc이고 셋째 크기는 넷째 크기 f의 동일한 배수 mf이고, 다섯째는 nc, 여섯째는 nf라고 한다면 첫째와 다섯째의 합은 둘째의 배수이고 셋째와 여섯째의 합은 넷째의 배수이다.

$$mc+nc=(m+n)c,\;\;mf+nf=(m+n)f$$

Proposition 3 If a first magnitude is the same multiple of a second that a third is of a fourth, and if equimultiples are taken of the first and third, then the magnitudes taken also are equimultiples respectively, the one of the second and the other of the fourth.

첫째 a와 셋째 c는 둘째 b와 넷째 d에 각각 같은 수 n을 곱한 배수이고, 첫째와 셋째에 같은 수 m을 곱하면 그들은 각각 c와 d에 같은 수를 곱한 것과 같다.

$a=nb,\;\;c=nd$이면 $ma=m(nb)=(mn)b,\;\;mc=m(nd)=(mn)d$이다.

곱셈에 대한 결합법칙이 성립함을 말하고 있다.

Proposition 4 If a first magnitude has to a second the same ratio as a third to a fourth, then any equimultiples whatever of the first and third also have the same ratio to any equimultiples whatever of the second and fourth respectively, taken in corresponding order.

첫째와 둘째, 셋째와 넷째가 이루는 비가 같다면 첫째와 셋째에 같은 수 $p$, 셋째와 넷째에 같은 수 $q$를 곱한 수가 이루는 비가 같다.

$a:b=c:d$이면 임의의 수 $p, q$에 대하여 $pa:qb=pc:qd$이다.

Proposition 5 If a magnitude is the same multiple of a magnitude that a subtracted part is of a subtracted part, then the remainder also is the same multiple of the remainder that the whole is of the whole.

크기가 뺀 부분이 뺀 부분의 크기에 같은 수 m를 곱한 것이라면, 남은 부분도 전체가 전체의 나머지에 같은 수 m을 곱한 것과 같다.

$x,\;\;y$는 크기, $m$은 임의의 수일 때, $m(x-y)=mx-my$

Proposition 6 If two magnitudes are equimultiples of two magnitudes, and any magnitudes subtracted from them are equimultiples of the same, then the remainders either equal the same or are equimultiples of them.

두 크기에 대하여 같은 수를 곱하고 그 곱들에서 원래의 크기에서 또 어떤 같은 수를 곱한 것을 빼면, 그들의 나머지들은 원래 크기이거나 또는 원래 크기에 같은 곱이다.

Proposition 7 Equal magnitudes have to the same the same ratio; and the same has to equal magnitudes the same ratio.Corollary If any magnitudes are proportional, then they are also proportional inversely.

크기가 같은 두 크기는 어떤 크기에 대해서든 같은 비율을 가진다. 그리고 어떤 크기든 간에 같은 크기의 크기는 같은 비율을 가진다.

Proposition 8 Of unequal magnitudes, the greater has to the same a greater ratio than the less has; and the same has to the less a greater ratio than it has to the greater.

크기가 다른 크기와 어떤 크기가 있다. 큰 것과 어떤 크기와의 비율은 작은 것과 어떤 크기와의 비율보다 더 크다. 또한 어떤 크기와의 작은 것에 대한 비율은 어떤 크기와 큰 것의 비율보다 더 크다.

Proposition 9 Magnitudes which have the same ratio to the same equal one another; and magnitudes to which the same has the same ratio are equal.

두 개의 크기가 어떤 크기에 대해서 비율이 같으면 두 개의 크기가 같다. 또한 어떤 크기가 두 개의 크기에 대한 비율이 같으면 두 개의 크기는 같다.

Proposition 10 Of magnitudes which have a ratio to the same, that which has a greater ratio is greater; and that to which the same has a greater ratio is less.

두 개의 크기의 어떤 크기에 대한 두 비율이 큰 비율이 더 크면 큰 비율의 크기가 더 크다. 또한 어떤 크기에 대한 두 개의 크기의 비율이 더 작은 비율의 크기가 더 크다.

Proposition 11 Ratios which are the same with the same ratio are also the same with one another.

두 비율이 어떤 비율과 같으면 그 두 비율은 서로 같다.

Proposition 12 If any number of magnitudes are proportional, then one of the antecedents is to one of the consequents as the sum of the antecedents is to the sum of the consequents.

여러 개의 여러 크기들이 서로 비례한다고 하자. 앞의 크기 모두를 더한 것과 뒤의 크기를 모두 더한 것의 비율도 그 비율과 같다.

Proposition 13 If a first magnitude has to a second the same ratio as a third to a fourth, and the third has to the fourth a greater ratio than a fifth has to a sixth, then the first also has to the second a greater ratio than the fifth to the sixth.

여섯 개의 크기에 대하여 첫 번째 크기와 두 번째 크기의 비율은 세 번째 크기와 네 번째 크기의 비율과 같고 세 번째 크기와 네 번째 크기의 비율이 다섯 번째 크기와 여섯 번째 크기의 비율 보다 크면 첫 번째 크기와 두 번째 크기의 비율도 다섯 번째 크기와 여섯 번째 크기의 비율 보다 크다.

Proposition 14 If a first magnitude has to a second the same ratio as a third has to a fourth, and the first is greater than the third, then the second is also greater than the fourth; if equal, equal; and if less, less.

첫 번째 크기와 두 번째 크기의 비율이 세 번째 크기와 네 번째 크기의 비율과 같다. 이때, 첫 번째 크기가 세 번째 크기보다 크면 두 번째 크기는 네 번째 크기보다 크며, 같으면 같고, 작으면 작다.

Proposition 15 Parts have the same ratio as their equimultiples.

어떤 두 개의 크기의 비율을 각 크기를 크기가 같은 임의의 개수로 나누자. 그러면 각각 나누어진 한 개의 크기의 비율은 어떤 두 크기의 비율과 같다.

Proposition 16 If four magnitudes are proportional, then they are also proportional alternately.

네 개의 크기에 대하여, 첫 번째 크기와 두 번째 크기의 비율이 세 번째 크기와 네 번째 크기의 비율이 같으면 첫 번째 크기와 세 번째 크기의 비율이 두 번째 크기와 네 번째 크기의 비율과 같다.

Proposition 17 If magnitudes are proportional taken jointly, then they are also proportional taken separately.

어떤 네 개의 크기에 대하여, 첫 번째와 두 번째 크기를 더한 크기와 두 번째 크기의 비율은 세 번째 크기와 네 번째 크기를 더한 크기와 네 번째 크기의 비율을 같으면, 첫 번째 크기와 두 번째 크기에서 두 번째 크기를 뺀 크기와 두 번째 크기의 비율은 세 번째 크기와 네 번째 크기를 더한 크기에서 네 번째 크기를 뺀 크기와 네 번째 크기의 비율이 같다. 즉, 첫 번째와 두 번째 크기의 비율은 세 번째와 네 번째 크기의 비율이 같다.

Proposition 18 If magnitudes are proportional taken separately, then they are also proportional taken jointly.

네 크기에 대하여, 첫 번째 크기와 두 번째 크기의 비가 세 번째 크기와 네 번째 크기의 비와 같으면 첫 번째와 두 번째 크기의 합과 두 번째 크기의 비는 세 번째와 네 번째 크기의 합과 네 번째 크기의 비와 같다.

Proposition 19 If a whole is to a whole as a part subtracted is to a part subtracted, then the remainder is also to the remainder as the whole is to the whole.Corollary. If magnitudes are proportional taken jointly, then they are also proportional in conversion.

두 개의 전체 크기의 비와 각각 크기의 각 부분과의 비가 같으면, 각각의 나머지의 비와 전체 크기의 비가 같다.

Proposition 20 If there are three magnitudes, and others equal to them in multitude, which taken two and two are in the same ratio, and if ex aequali the first is greater than the third, then the fourth is also greater than the sixth; if equal, equal, and; if less, less.

세 개의 크기와 또 다른 세 개의 크기에 대하여, 이들 차례로 크기의 두 개씩의 비율이 같다고 하자. 그러면 첫 번째 크기가 세 번째 크기 보다 크면 네 번째 크기가 여섯 번째 크기보다 크고 같으면 같고, 작으면 작다.

Proposition 21 If there are three magnitudes, and others equal to them in multitude, which taken two and two together are in the same ratio, and the proportion of them is perturbed, then, if ex aequali the first magnitude is greater than the third, then the fourth is also greater than the sixth; if equal, equal; and if less, less.

세 개의 크기가 있고 또 다른 세 개의 크기가 있다. 그리고 그 두 개의 크기의 비율이 서로 엇갈려 있다고 하자. 그러면 첫 번째 크기가 세 번째 크기 보다 크면 네 번째 크기도 여섯 번째 크기보다 크고, 같으면 같고, 작으면 작다.

Proposition 22 If there are any number of magnitudes whatever, and others equal to them in multitude, which taken two and two together are in the same ratio, then they are also in the same ratio ex aequali.

임의 수의 개수 만큼 크기가 있고, 또 다른 크기가 같은 개수만큼 있다고 하자. 이들 크기 두 개씩 비율을 구할 수 있고, 그 비율이 순서대로 같다고 하자. 그러면 같은 위치에 있는 크기의 비율은 같다. 즉, 첫 째와 맨 마지막 비율이 같다.

Proposition 23 If there are three magnitudes, and others equal to them in multitude, which taken two and two together are in the same ratio, and the proportion of them be perturbed, then they are also in the same ratio ex aequali.

세 개의 크기와 또 다른 세 개의 크기에 대하여, 첫 번째와 두 번째 크기 비율이 네 번째와 여섯 번째 크기의 비율이 같고, 두 번째와 세 번째 크기의 비율이 네 번째와 다섯 번째 크기의 비율과 같다고 하자. 그러면 첫 번째와 세 번째 크기의 비율은 네 번째와 여섯 번째 크기의 비율과 같다.

Proposition 24 If a first magnitude has to a second the same ratio as a third has to a fourth, and also a fifth has to the second the same ratio as a sixth to the fourth, then the sum of the first and fifth has to the second the same ratio as the sum of the third and sixth has to the fourth.

여섯 개의 크기에 대하여, 첫 번째와 두 번째 크기의 비율은 세 번째와 네 번째 크기의 비율과 같고, 다섯 번째와 두 번째 크기의 비율은 여섯 번째와 네 번째 크기의 비율과 같다고 하자. 그러면 첫 번째와 다섯 번째 크기를 더한 크기와 두 번째 크기의 비율은 세 번째와 여섯 번째 크기를 더한 크기와 네 번째 크기와의 비율과 같다.

Proposition 25 If four magnitudes are proportional, then the sum of the greatest and the least is greater than the sum of the remaining two.

네 개의 크기에 대하여, 첫 번째와 두 번째 크기의 비율이 세 번째와 네 번째 크기의 비율과 같다. 그러면 가장 큰 크기와 가장 작은 크기의 합의 크기는 나머지 두 크기의 합보다 크다.

Guide for Book V

Background on ratio and proportion

Book V covers the abstract theory of ratio and proportion. A ratio is an indication of the relative size of two magnitudes. The propositions in the following book, Book VI, are all geometric and depend on ratios, so the theory of ratios needs to be developed first. To get a better understanding of what ratios are in geometry, consider the first proposition VI.1. It states that triangles of the same height are proportional to their bases, that is to say, one triangle is to another as one base is to the other. (A proportion is simply an equality of two ratios.) A simple example is when one base is twice the other, therefore the triangle on that base is also twice the triangle on the other base. This ratio of 2:1 is fairly easy to comprehend. Indeed, any ratio equal to a ratio of two numbers is easy to comprehend. Given a proportion that says a ratio of lines equals a ratio of numbers, for instance, A : B = 8:5, we have two interpretations. One is that there is a shorter line CA = 8C while B = 5C. This interpretation is the definition of proportion that appears in Book VII. A second interpretation is that 5 A = 8 B. Either interpretation will do if one of the ratios is a ratio of numbers, and if A : B equals a ratio of numbers that A and B are commensurable, that is, both are measured by a common measure.

Many straight lines, however, are not commensurable. If A is the side of a square and B its diagonal, then A and B are not commensurable; the ratio A : B is not the ratio of numbers. This fact seems to have been discovered by the Pythagoreans, perhaps Hippasus of Metapontum, some time before 400 B.C.E., a hundred years before Euclid’s Elements.

The difficulty is one of foundations: what is an adequate definition of proportion that includes the incommensurable case? The solution is that in V.Def.5. That definition, and the whole theory of ratio and proportion in Book V, are attributed to Eudoxus of Cnidus (died. ca. 355 B.C.E.)

Summary of the propositions

The first group of propositions, 1, 2, 3, 5, and 6 only mention multitudes of magnitudes, not ratios. They each either state, or depend strongly on, a distributivity or an associativity. In the following identities, m and n refer to numbers (that is, multitudes) while letters near the end of the alphabet refer to magnitudes.

V.1. Multiplication by numbers distributes over addition of magnitudes.

V.2. Multiplication by magnitudes distributes over addition of numbers.

V.3. An associativity of multiplication.

V.5. Multiplication by numbers distributes over subtraction of magnitudes.

V.6. Uses multiplication by magnitudes distributes over subtraction of numbers.

The rest of the propositions develop the theory of ratios and proportions starting with basic properties and progressively becoming more advanced.

V.4. If w : x = y : z, then for any numbers m and n, mw : mx = ny : nz.

V.7. Substitution of equals in ratios. If x = y, then x : z = y : z and z : x = z : y.

V.7.Cor. Inverse proportions. If w : x = y : z, then x : w = z : y.

V.8. If x < y, then x : z < y : z but z : x > z : y.

V.9. (A converse to V.7.) If x : z = y : z, then x = y. Also, if z : x = z : y, then x = y.

V.10. (A converse to V.8.) If x : z < y : z, then x < y. But if z : x < z : y, then x > y

V.11. Transitivity of equal ratios. If u : v = w : x and w : x = y : z, then u : v = y : z.

V.12. If x1:y1 = x2:y2 = ... = xn : yn, then each of these ratios also equals the ratio (x1 + x2 + ... + xn) : (y1 + y2 + ... + yn).

V.13. Substitution of equal ratios in inequalities of ratios. If u : v = w : x and w : x > y : z, then u : v > y : z.

V.14. If w : x = y : z and w > y, then x > z.

V.15. x : y = nx : ny.

V.16. Alternate proportions. If w : x = y : z, then w : y = x : z.

V.17. Proportional taken jointly implies proportional taken separately. If (w + x):x = (y + z):z, then w : x = y : z.

V.18. Proportional taken separately implies proportional taken jointly. (A converse to V.17.) If w : x = y : z, then (w + x):x = (y + z):z.

V.19. If (w + x) : (y + z) = w : y, then (w + x) : (y + z) = x : z, too.

V.19.Cor. Proportions in conversion. If (u + v) : (x + y) = v : y, then (u + v) : (x + y) = u : x.

V.20 is just a preliminary proposition to V.22, and V.21 is just a preliminary proposition to V.23.

V.22. Ratios ex aequali. If x1:x2 = y1:y2, x2:x3 = y2:y3, ... , and xn-1:xn = yn-1:yn, then x1:xn = y1:yn.

V.23. Perturbed ratios ex aequali. If u : v = y : z and v : w = x : y, then u : w = x : z.

V.24. If u : v = w : x and y : v = z : x, then (u + y):v = (w + z):x.

V.25. If w : x = y : z and w is the greatest of the four magnitudes while z is the least, then w + z > x + y.

Logical structure of Book V

| Book V is on the foundations of ratios and proportions and in no way depends on any of the previous Books. Book VI contains the propositions on plane geometry that depend on ratios, and the proofs there frequently depend on the results in Book V. Also Book X on irrational lines and the books on solid geometry, XI through XIII, discuss ratios and depend on Book V. The books on number theory, VII through IX, do not directly depend on Book V since there is a different definition for ratios of numbers.Although Euclid is fairly careful to prove the results on ratios that he uses later, there are some that he didn’t notice he used, for instance, the law of trichotomy for ratios. These are described in the Guides to definitions V.Def.4 through V.Def.7. * Some of the propositions in Book V require treating definition V.Def.4 as an axiom of comparison. One side of the law of trichotomy for ratios depends on it as well as propositions 8, 9, 14, 16, 21, 23, and 25. Some of Euclid’s proofs of the remaining propositions rely on these propositions, but alternate proofs that don’t depend on an axiom of comparison can be given for them. Propositions 1, 2, 7, 11, and 13 are proved without invoking other propositions. There are moderately long chains of deductions, but not so long as those in Book I. The first six propositions excepting 4 have to do with arithmetic of magnitudes and build on the Common Notions. The next group of propositions, 4 and 7 through 15, use the earlier propositions and definitions 4 through 7 to develop the more basic properties of ratios. And the last 10 propositions depend on most of the preceding ones to develop advanced properties. |